San Francisco Chronicle

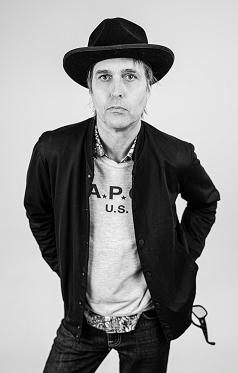

“San Francisco,” says Chuck Prophet, “is a great place for a musician to live.” He backs up his claim, in typical fashion, with numerous diversionary tales of San Franciscans he’s known, music he’s heard and places where he’s been, washed dishes and parked cars. He loves the gravitational pull the city has on “people with a freak flag to wave.” If a lot of artists on the fringe were driven out during the dot-com era, he reckons that that’s starting to shift.

Prophet, 43, was born and raised in Orange County until his family moved north. He went to high school in the East Bay and college in San Francisco and never left. “I don’t like to brag, but Stephanie and I do have a rent-controlled apartment,” he says. It’s in the Lower Haight, or if you’re a real estate agent, Duboce. “And I have done the math and I’ve come to the conclusion that to have a rent-controlled apartment has about the same value as a Ph.D. over time.”

Stephanie Finch, Prophet’s wife, a singer, writer and keyboard player, is also part of the city’s music scene. Recently the pair spent a month touring Europe with Prophet’s band, in a van. “I tell you, you drive 2,000 miles in a Ford Econoline at a stretch and it’s either gonna bring you together or pull you apart,” he says. The couple, who first recorded together on Prophet’s 1990 debut album, “Brother Aldo,” celebrated their 10th wedding anniversary this year.

They’re back home for just a couple of days, to repack, convert their euros to dollars and play a special hometown show at the Make-Out Room, with free Mexican food (Prophet, who hired a taco truck, says, laughing, that he’s still paying it off). Then it’s back on the road for a U.S. tour to promote Prophet’s new album, “Soap and Water.” It’s been picking up accolades here and abroad from the British music press, where he’s long been a star, to mainstream American media (Entertainment Weekly called it “excellent”).

“I wouldn’t - maybe it’s superstition - utter anything like that out loud, but people have been reacting to this album,” Prophet says. “It’s an elusive thing, making records, and I don’t know what it is, but I do know that records are never really finished, they’re just abandoned. At a certain point it’s like ‘I haven’t got any more time or money, I give up.’ Or I could push it around on my plate until I lose my appetite or I could just cut it loose and it can fend for itself. But then you do make a point of killing yourselves (with touring) at least once behind every record. You know, give it the college try.”

“Soap and Water” was recorded in two very different music cities, San Francisco and Nashville. One has the bay and Rainbow Grocery; the other is landlocked and has Christian supermarkets. “Aside from the country music community, it does have a lot of churches,” Prophet says. And gospel singers. That’s why when he suggested to his producer that they overdub a choir - “I’d been listening to ‘Jesus Christ Superstar,’ ‘Godspell’ and a group called the English Congregation who, it turns out, were neither English nor a congregation” - Nashville was the place to go.

But Prophet wanted a choir without real singers. They got 27 schoolkids into the studio “with the aid of only some M&Ms;and pizza. The extra level of irony they give to songs like ‘Let’s Do Something Stupid’ just made the whole record that much more perverted somehow. I loved it.”

For the past couple of years, Prophet has been spending an inordinate amount of time in Nashville. He produced and guested on the acclaimed new album by country singer Kelly Willis (“Translated From Love”). He has also been co-writing country songs. “I’m Gone,” written with Kim Richey, was a Top 40 hit for Cyndi Thompson. “I’ve got the gold record in the bathroom to prove it.”

It was his music publisher who first suggested he go to Nashville and write country songs, “when it became pretty clear that they weren’t going to get much of their advance back from the record I put out.” His response was, “Yeah, and after that I can go to Hollywood and write a screenplay,” but he did and he liked it.

“It’s a funny community; I do find myself writing with people that in real life I probably wouldn’t have anything in common with at all. But I’ve since made some friends out there and been lucky enough to write with some really great writers.”

What drew him back was that his record label had dropped him. He burnt out from touring with “Age of Miracles,” the last album he recorded for it. “Things kind of started unraveling and I didn’t know if I even wanted to do it again,” he says. He spent the next year “trying to figure out if there was other stuff to do.” There was.

Besides Nashville, there was the reunion of his roots-rock band Green on Red and a collaboration with Austin, Texas, singer-songwriter Alejandro Escovedo, with whom he has been writing and recording an album. He signed a publishing deal for a book “chronicling life in motion - gathering road stories from different artists; whether you stay in five-star hotels or whether you have a tennis shoe for a pillow in the back of van.” He brushed off his own small label, Belle sound, usually reserved for his and Stephanie’s projects, and released an album by East Bay singer-songwriter Sonny Smith (“Fruitvale”). He tried writing a screenplay with Happy Sanchez. He landed a role in San Francisco filmmaker Miles Matthew Montalbano’s “Revolution Summer,” “playing this deranged drug dealer. I was just doing my best Dennis Hopper, really.”

“I have an addictive personality, but music is probably the healthiest addiction I’ve had.” He’s kicked the rest. “And I think my biggest fear is I’d have to stop. After all this manic activity, it turns out that I do have a dark need to make records anyway - because we made this record without a record deal, just pulled it together - and I have a dark need to drive around the world in a van like I’m 22. And to be honest with you, I’m good at it, too. I’m good at staring out of a window for long stretches.”

He smiles. “People always ask me, ‘Don’t you think you should be bigger?’ I don’t even think of that, I just think of the next record.

“When we first started playing music and we were living like community college students, our goal was always to live like graduate students, so in that sense, we’ve held on.”

But, he adds, “it’s still hell trying to find a place to park the van.”

3_238_159auto_s_c1.jpeg)