Pure Music

JUNGLE JIM AND THE VOODOO TIGER

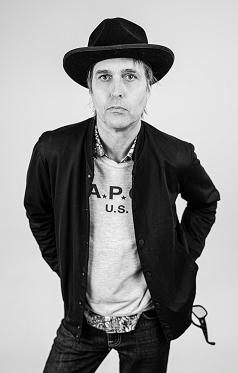

Jim Dickinson

Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be. Dwelling on the glories of the past, whatever the decade currently in fashion, pales before the glories of the present with its paradigm shifts and all-access Internet. One thing I do miss in the recent and current decade is “characters”: that is, people who don’t fall into types; folks who by dint of intelligence, mixed with experience and a unique vision of the world, carve out a personal place in it—men like Jim Dickinson.

It would be easy to write him off as a mere roots-rock legend. The legend would start at the Sound of Memphis Studio in the late Sixties, where, with Charley Freeman, Tommy McClure, and Sammy Creason, he formed the rhythm section known as the “Dixie Flyers.” The Flyers moved to Miami, Florida, as the Atlantic Records house band backing such artists as Aretha Franklin, Sam & Dave, and Jerry Jeff Walker. After leaving the Flyers, Dickinson returned to Memphis, and began a producing career, working with Ry Cooder and Big Star. His work with the latter no doubt appealed to later clients like Green On Red, and The Replacements. And, oh yeah, Dickinson recorded “Wild Horses” with the Rolling Stones.

In true “character” fashion, these facts don’t begin to sum up the man. You might be surprised that he studied drama at Baylor University—unless you thought about it for a minute. He has released two solo records before this as James Luther Dickinson, thirty years apart (take that, T Bone). The more recent, 2002’s Free Beer Tomorrow, contains a song, “Ballad of Billy and Oscar,” about an imagined meeting between Billy the Kid and Oscar Wilde, written by the art critic Dave Hickey. Starting to get the picture? Pigeonholing just don’t work here.

Jungle Jim and the Voodoo Tiger continues in the spirit of both the legend and the character. Having raised his own band (sons Luther and Cody Dickinson of the North Mississippi Allstars) he employs them here on a romp through tunes that suit his style. One of the signs of a true character is that they can take a song that has been done to death, like Terry Fell’s “Truck Drivin’ Man,” and inject new life into it—and not just by adding a hardly heard verse. Rarely writing his own songs, Dickinson always includes a Bob Frank tune, here opening with a rendition of “Redneck, Blue Collar,” a vision of the workingman as hard to pin down as James Luther himself. The late Eddie Hinton helps Dickinson and company define Southern soul with his “Can’t Beat the Kid.” Chuck Prophet, one of the few new characters to emerge in the last twenty years, contributes a tender ballad, “Somewhere Down the Road.”

With a voice that is more gruff attitude than mellifluous melisma, Jim Dickinson demonstrates that attitude is enough if you have the goods to back it up. Ask fellow characters like Bob Dylan, Ry Cooder, and Keith Richard—they will testify that the man has the goods in spades.

3_238_159auto_s_c1.jpeg)