The Hurting Business

Ex-Green on Red mainstay Chuck Prophet continues his solo metamorphosis with The Hurting Business

Prophet comes clean: “Rock ‘n’ roll has just gotten too precious.”

The first thing you notice talking to Chuck Prophet, naturally, is his voice. Not so much the way it sounds—a raspy, unfettered bark—but the attitude it projects. His is the tone of a polite cynic—filled with gallows humor, self-deprecation and a world-weary indifference. The kind that seems logical given a lifetime of cult success and junkie excess.

The L.A.-born Prophet spent nearly a decade with ‘80s psychedelic cowboys turned roots avatars Green on Red, most of it riding shotgun with partner/singer Dan Stuart. By the time the group ground to a halt some nine years and 10 albums after it had begun, GOR had yielded a rabid underground following (especially in the U.K.), a vaunted critical legacy and little in terms of tangible success.

Meanwhile, Prophet had become the victim of the clichéd rock ‘n’ roll existence, plunged into the depths of a herculean heroin habit that left him at death’s door.

But by the mid-‘90s, life found Prophet clean, married and in the throes of a fruitful, if overlooked, solo career.

Terminally deadpan, the lanky guitarist brightens when discussing the genesis of his fifth and latest album, The Hurting Business—a radical and triumphant departure from the journeyman country-rock of his past.

The idea for the record was hatched after Prophet returned home from a lengthy tour in support of 1997’s Homemade Blood. In his mind, he had already conceived a loose-knit concept album which would take an aural shift away from the innately folkish charm and Exile-era Stones aphorisms that had marked his previous work.

“I had a sound in my head,” recalls Prophet. “And I wanted to take a cinematic approach with it.”

Prophet’s primary influence in creating The Hurting Business wasn’t musical, but rather inspired by Danish director Lars Von Trier’s “Dogma 95” film movement. Stylistically rooted in naturalism and realism, Von Trier’s pictures (most notably Breaking the Waves) focus on the vagaries of contemporary life, filmed without effects, using natural lighting and jarring movements provided by hand-held cameras.

To help him achieve a similarly original and vertiginous feel on wax, Prophet hooked up with Jacquire King, an engineer and desktop recording wizard who helped shape Tom Waits’ grim-and-grand weeper Mule Variations.

“Part of working with him was a desire to get out of the normal staid studio recording process. We just kind of took my original four-track sketches of the songs and loaded them into the computer and were able to go in and add and cut stuff wherever we wanted.”

Prophet also strove to match the organic feel of the Dogma style by capturing a natural ambiance on his vocal tracks, recording them everywhere from the front seat of his car to a bathroom stall. “I’ve never been one to require mood lighting or candles when I sing,” he notes with a chuckle. “But sometimes you do feel the need to extend the mike cable a little bit so you can get that same feeling you get when you’re sitting there singing by yourself.”

To complete his vision, Prophet decided he needed something more than the jagged guitar chords he’d long relied on. He found what he sought in the lexicon of electronic music—the stutters and starts of turntables and elasticized grooves of machine-made beats.

“That was definitely inspired by a lot of things I’ve been hearing,” says Prophet, rattling off a list of names that range from hip-hop eclectic Dr. Octagon to neo-blues experimentalist Jon Spencer.

“It’s at the point where people are taking traditional songwriting or traditional structures and figuring out ways to twist and turn them sideways. That’s always the fun part—kicking the song around and wrestling with it. Seeing how much you can beat it up beyond recognition before it gets worse.”

Much of Business is augmented by loops, scratching and the occasional sample—the bulk of them provided by prominent Bay Area turntablist DJ Rise. The album’s cut-and-paste fusion teems with an overall quality that mimics the laid-back jazz cool and foreboding sonic textures of Portishead and the Sneaker Pimps.

While the move may smack of an aging roots-rocker’s bid for postmodern relevancy, Prophet incorporates the subtle electronic touches so deftly, they seem less an intrusion or distraction than just another instrument at his disposal.

If anything, the songs lend themselves to such tinkering as Prophet’s effort comes off more memorably than Joe Strummer’s Rock, Art and the X-Ray Style, and more genuine than the Stones’ Bridges to Babylon flirtations with the Dust Brothers—both forays by traditional rockers into similar loop-and-sample territory.

But beyond modern accouterments, the foundation of The Hurting Business is rooted in a bedrock of deep soul sounds—black and white, North and South. Songs that draw on greasy R&B, from Muscle Shoals to Harlem, and a strain of late ‘60s country/pop that Prophet calls “housewife goth.” “Bobbie Gentry, Tom T. Hall, Dusty Springfield, Jimmy Webb—all the great story songs from that era.”

Consequently, there is a heavy emphasis on craft. Half the album’s 12 songs clock in at three minutes or less, a structure that Prophet regards as vital to the essence of his work.

“Rock ‘n’ roll has just gotten too precious. I hear records nowadays and the fades are like a minute. If you go back and listen to James Brown or Charles Wright, Betty Harris, Lee Dorsey, any of the stuff I was soaking in the couple years where I was working toward this record, they’re like two and a half minutes long—that’s it. And when they’re over, all you want to do is put the needle back to the beginning. That’s the kind of record I wanted to make.”

Prophet should take heart; The Hurting Business is exactly that kind of album, one that invites frequent and repeated listenings, yet provides new revelations with each spin.

Kicking off with the funky Ennio Morricone-influenced opener, “Rise” (“A change, a change is gonna come/Those very words once left me numb”), Prophet fashions a sometimes dark, often funny narrative of modern life, seething with urban tension, and sprinkled with caustic insights and pop culture references.

The title track, an insistent farfisa-maraca number that hints at Beck, were Mr. Hansen in the midst of a serious Sir Douglas Quintet jag. A he-did/she-did tale of fraught relationships and bruised romance (“You hurt me, baby, and I hurt you/Sometimes we fake, sometimes we jab/Sometimes we bounce right off the mat”), it takes its name from the unlikeliest of sources, a Mike Tyson quote.

“It was during a press conference after he bit off Evander Holyfield’s ear. They asked him if he wanted to apologize, if he felt any remorse about what he did. His reaction was just belligerent and insolent: ‘You understand, I’m in the hurting business, that’s my job,’” says Prophet in sotto voce, imitating Tyson. “He thought he was doing his job in there. I liked that. I don’t know how it relates to what boys and girls do to each other, but it ended up in my notebook.”

Prophet’s vocals—which normally split the difference between Tom Petty’s redneck whine and Kurt Wallinger’s British drone—take on a variety of hues here: the somber baritone of “Rise”“; the funky drawl of “Diamond Jim”“; the angelic croon of ‘Dyin’ All Young.”

On “It Won’t Be Long,” Prophet’s singing recalls Iggy Pop’s dry, craggy tone. Ironically, the song is a more successful stab at the kind of moody string atmospherics that the middle-aged Stooge attempted on last year’s career nadir, Avenue B.

The song’s theme, like much of Business, is imbued with a sense of irreverent topicality—in this case, it’s the world of the confrontational daytime talk show. “What we were trying to imagine was what the mother lode of all hangovers would be like if you stood naked on Jenny Jones and embarrassed yourself in front of a whole nation,” says Prophet, breaking into a coarse laugh. “What would the morning after that be like, when you realized what you’d actually done?”

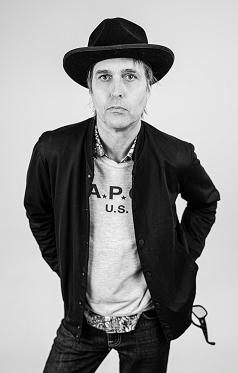

Peter Anderson

Pills and booze: Prophet (left) and Stuart with Green on Red in 1989

While the subject matter may be bleak—Prophet characterizing it as “trailer park trash with high Arbitron ratings” and “the sad beauty of freak encounters recollected”—the song retains a light, almost absurdist lyrical quality: “I like T-Bone Walker/I like Wonder bread/I like to quote back in your face/All the things you never said.”

Elsewhere, Hammond organ colors the deathly revenge anthem “Lucky” (“I’d like to get Lucky/Get my fingers ‘round his throat”), its dark, smoky verses and skewed sonics surrendering to a chorus that arches up toward classic pop territory.

Not surprisingly, the record does stumble upon some of Tom Waits’ patented gruff ‘n’ clang, with the jagged blues and vocoder/megaphone intonations of “La Paloma” and the funky “Shore Patrol” (another vaguely Beck-ish sounding number).

At his best, Prophet seems capable of synthesizing his many influences—musical and lyrical—into a uniquely original vision. When he does, the results are the apogee of understated brilliance, as on the album’s centerpiece, “Apology.”

A languid mesh of warm bass and Mellotron, the song takes the universal human need for forgiveness and turns the concept on its ear with a litany of comical examples: “CBS from the MTV,” “the shoulder from the road,” “the Cancer from the Scorpio.”

But the moment that best captures Prophet’s ironic worldview comes after a verse in which he opines that “someday soon the Vatican is gonna call”—an allusion to the recent papal apology for the Catholic Church’s toleration of the Holocaust. Prophet follows that heady reference with a bridge that asks, “How can I swallow every little thing she says?/She don’t even know Elvis from El Vez.”

It’s the kind of uncommonly literate moment that bridges hard-edged romanticism and precise musical syntax, while plumbing the depths of pop arcana.

“When you start talking about when the Jews are going to get an apology form the Vatican, you can’t follow that up with anything too heavy,” says Prophet. “You gotta get into something as pathetic as falling out with a girl because she doesn’t know the difference between Elvis and El Vez. Some people, man, that’s how small their world is.”

Surprisingly, Prophet’s signature guitar work is downplayed on The Hurting Business. The album boasts few traditional solos, as the instrument is more a character actor than a featured star in Prophet’s wide-screen production. His twangy runs and subtle fills are still there, but they never rise above the songs, married instead to a bed of keyboard sounds, clipped percussion and ghostly background vocals (provided by a studio cast that includes Prophet’s wife, singer/pianist Stephanie Finch; bassists Roly Salley and Andy Stoller; American Music Club’s Tim Mooney; and longtime drummer Paul Revelli, among others). For Prophet—a man who made his early reputation as a six-string hot shot—the lack of over-the-top fretwork isn’t a problem.

“My tendency is to turn the guitars down. I hear that sometimes with Lindsey Buckingham or J.J. Cale—where it sounds like they’re just a little bit underneath everything. I don’t know why, that’s just where my sensibilities lie. It’s not that way onstage, though,” he says.

Like a number of his fellow roots-rockers, Prophet has long faced an unusual career quandary; all but ignored in his home country, he’s maintained a healthy following—even minor star status—overseas.

“I’ve got a love/hate relationship with Europe. I mean, I enjoy the success we have over there, but I’m not making this music thinking what someone in Paris would like. I’m making American music,” he offers adamantly. “After a while, you start walking around thinking you’re crazy because you’re not connecting with more Americans. But I think we’ve sort of turned that around with this record. It’s been really gratifying to go to shows and see a lot of people, especially when they speak English.”

Since its January release, The Hurting Business helped boost his profile in the U.S., earning the kind of breakthrough hosannas from critics that Prophet supporters have long demanded. Despite that, his sales remain modest, a situation that he feels will be remedied over time.

“The thing about being a solo artist is you tend to get discovered and rediscovered. I think the real challenge is building a nice body of work that people can tap into anywhere along the line.”

Prophet’s solo catalogue is impressive, running from 1990’s country quaint Brother Aldo, through the Cosmic American muse of 1993’s Balinese Dancer, continuing with 1995’s unassumingly retro Feast of Hearts and up to his previous long player, the suburbia study Homemade Blood.

Unfortunately, the bulk of those titles are hard to find on these shores. Only Business is readily available, and it was originally recorded for the U.K.‘s Cooking Vinyl label, only later to be licensed for American release by Hightone.

Still, Prophet’s popularity is flowering in many quarters, thanks in part to the cult surrounding Green on Red, one that continues to grow on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1995, China Records released a GOR best-of; in 1997, Germany’s Normal issued Archives Vol. 1, a retrospective collecting demos, B-sides and live tracks; in 1998, Edsel U.K. put out the group’s last four albums as a pair of special-edition two-fers. And later this year, Restless Records will issue an expanded, remastered version of 1985’s alt-country pioneering Gas, Food & Lodging.

Prophet (who hooked up with the originally Tucson-based Green on Red in L.A. in the mid-‘80s) looks back at his time with the group fondly. Still, he has no regrets about GOR’s 1992 demise.

“You can only drag your adolescence so far into your adulthood. Being in a band is like living with your parents. You gotta move out of the house before people start talking—‘How old is he? 35 years old and he’s still living at home!’” he says, amid gales of laughter. “It’s just natural to get out of it. Plus, nobody can break me up. I’ve tried. Believe me, I tried to break myself up and it’s hard to do.”

While the arc of his work clearly proves that Prophet has benefited from solitude, he hasn’t remained cloistered. On the contrary, he’s been an in-demand collaborator on projects ranging from alt-country sweetheart Kelly Willis’ 1999 comeback LP What I Deserve (Prophet plays on the album and co-wrote its “Got a Feeling for Ya” with Southern soul composer Dan Penn) as well as hired gun for alterna-rockers Cake and Hollywood songwriter cynic Warren Zevon.

“It’s always flattering when the phone rings,” says Prophet. “Sometimes you do it just to pay the utility bills and sometimes you get lucky and get to work with somebody like Kelly Willis out of the blue, and it ends up being really rewarding.”

Prophet also recently returned to the group fold, with an all-star contingent known as the Raisins in the Sun. Featuring legendary Memphis pianist/producer Jim Dickinson (Replacements, Big Star), knob-turning tandem Sean Slade and Paul Kolderie (Uncle Tupelo, Radiohead), singer/songwriter Jules Shear, and Dylan rhythm foils Harvey Brooks and Winston Watson, the group convened in a Tucson recording studio for two weeks in May 1999, with the notion of writing and recording an album from scratch.

“That was a leap of faith for everybody,” says Prophet of the sessions. “I think we were all prepared to go down to Tucson and come away with nothing.”

Instead, the collective came away with a self-described “10 slices of rock and soul” that are tentatively scheduled for release on Rounder Records.

Prophet’s immediate plans include the long-delayed completion of the debut album from Go-Go Market, a collaboration with wife Finch that he describes as “fulfilling a Brill Building jones.”

A follow-up to Business is also in its early stages. Instead of again taking the redacted studio route, Prophet plans to write and record a more ornate and traditional album, one that will feature fleshed-out arrangements, horns and a string section.

It’s hard not to marvel at Prophet’s versatility and output. It seems especially remarkable for a man once regarded as the epitome of wasted, junkie cool. The same Chuck Prophet who once denounced “rehab” as artistic immolation on the pages of Melody Maker.

“In a lot of ways I feel like I’m crazier now than I was back then—I’m just not on drugs anymore,” he says, laughing. “I’m off my medication and I feel like I’m much more dangerous now. I really do.”

3_238_159auto_s_c1.jpeg)