JamBase

Chuck Prophet ain’t no household name. Despite putting his shoulder into rock & roll since the late ‘70s with proto-Americana pioneers Green On Red, he remains a San Francisco treat known to a devout following and a coterie of fellow musicians who recognize what a true blue rocker Prophet is. He’s released three of the finest albums of the new millennium – 2000’s The Hurting Business, 2002’s No Other Love and 2004’s Age of Miracles - and his latest, Soap and Water [released October 2 on Yep Roc Records], looks to make it four. With Prophet, everything is in its right place. In the past decade he’s taken his roots rock beginnings into increasingly experimental terrain, juxtaposing boogie riffs with turntables, acoustic guitars with fuzzbox vocals. Like the man himself, the curves are always subtle and infused with a sense of divine laughter.

Prophet holds on tight until material is ripe, only releasing a new slab every couple years. His albums are creepers, where you might not realize just how good they are until you start pulling off individual cuts and see how they shine next to the work of others.

“I know I never let go of them until there’s a fair amount of blood on the floor. But that doesn’t make ‘em better! Music’s funny like that. There’s a kind of abstract-expressionist-cubist-blues approach where if you don’t connect all the dots and use a ruler there’s still some mystery left to the record. I think that’s the thing that makes people return, where more is revealed each time. I think good pop music sounds great the first listen but oftentimes you burn out on it. There’s no mystery to return to,” offers Prophet. “I like The Cars and ABBA and stuff like that but albums like Music From Big Pink or Tonight’s The Night are the ones that come into your mind and you continually return to.”

These are albums that ask the listener to make a leap with them. Every sentence isn’t strictly declarative and fresh, personal associations emerge over time. It’s music that rises above mere entertainment or distraction into the realm of philosophy and psychology. And in the best instances, we can still dance to it.

“As long as there’s something concrete there it’s fine. The music I like least is the purposefully obtuse indie rock or soundscapey stuff. That’s just me, but I still listen to Johnny Cash and Leonard Cohen and Some Girls [Rolling Stones]. In general, there’s just too much recording going on. Not everything needs to be preserved,” says Prophet. “It’s happening with filmmaking, too. At the same time, with the advent of video cameras and desktop editing you started to see movies like Hoop Dreams, which wouldn’t have existed otherwise and are just beyond words. I guess it’s just a whole lot of work for the consumer now [laughs].”

We’re rising and we’re falling

Falling and we’re rising

Lost on the invisible sea

A thousand stolen kisses

A crime without a witness

Throw me overboard captain would you please

I just can’t stand myself

Soap and Water draws palpably upon love and lust, which are given equal gravity in Prophet’s work, blasting off with the one-two punch of “Freckle Song,” a bright spot of late ‘70s Stones chug, and “Would You Love Me?,” tattered gospel for the faithless. While the tendency is to focus on either love or sex exclusively, Prophet commingles the two in a truly Gnostic fashion.

“Mothers need to hold their children. They need to feel that skin-on-skin thing, otherwise you breed some real monsters,” muses Prophet. “There’s a thing with my songs where they could be about women or about God or mom in an interchangeable way. It’s all there if you step back and squint at the songs. ‘Would You Love Me?’ was one of the last songs that went on the record, and was inspired by Anna Nicole Smith. She was everywhere in the media, and she was tragic. She died of a broken heart. Kinda reminded me a little bit of Elvis. [These type of figures] help us get out of ourselves. We think, ‘I’m fucked up but I’m not THAT fucked up.’ We need those people. We need to drag them out into the city square and stone them. Everybody will feel better.”

Prophet’s tone is mocking but there’s a sliver of ugly truth to his words. One wonders if we’re on our way back to coliseums where the rejected and downtrodden are forced to bloody themselves for the amusement of a desensitized world. “It’s already happening,” says Prophet. “Bin Laden or whatever, the boogie man is something people just have a need to create. It’s a scary part of our human nature. We can’t love ourselves enough to love mankind.”

One of the chief lures of Prophet’s work is a sense that all the fundamentals of strong musicianship - arranging, songwriting, performance and production - are always in place. There’s a rib-sticking fullness to everything he does that’s grown progressively stronger with each solo release.

“I cast each song like its own movie, and I try to find the characters to make it come alive. I hope there’s something about it that can keep me interested,” Prophet says. “I get a lot of ideas, start a lot of songs or push things around on my plate, but I don’t always have the energy to wrestle it all the way to the ground [laughs].”

Mothers need to hold their children. They need to feel that skin-on-skin thing, otherwise you breed some real monsters. There’s a thing with my songs where they could be about women or about God or mom in an interchangeable way. It’s all there if you step back and squint at the songs.

This reminds me of “Tough Company,” the opening poem from Charles Bukowski’s Play The Piano Drunk Like A Percussion Instrument Until The Fingers Begin To Bleed A Bit, where unfinished poems are “like gunslingers” that mill around his apartment waiting for him to finish them. Prophet chuckles and says, “I love that! I think early on he was more prone to pour a poem from beaker to beaker more times, and I love it. But I also love his later years where he was more impressionistic. That’s kinda the way I feel about Lucinda Williams right now. I love it all. I heard her sing ‘Pineola’ [from 1992’s Sweet Old World] the other night but I also love the stuff off her new record, which isn’t as chiseled.”

As he regards his own evolution, Prophet candidly responds, “I’m just getting the hang of it. I write better for my voice now. I think I’ve just grown into myself. I suppose early on I was more Dylan-esque or whatever but now there’s a straighter line that runs through the songs. I have great admiration for John Prine and Randy Newman. I try to write more the way people talk. We’re in an era where entertainment is just killing us. I think people have a need to be told stories, and that won’t ever change. It’s part of human nature and will continue to be. Keeping that in mind, it’s easier to make relevant records. Or records that are fun.”

“I asked my friend Dr. Frank of the Mr. T Experience - who’ve probably made 20 records - if he thought in the year 2007 it was possible to make relevant rock & roll. He’s a bit of an intellectual and he said, ‘Well, if it’s fun it’s relevant, right?’ And I had to agree,” says Prophet.

As a songwriter who lives in these troubled times, Prophet tries to avoid delivering political polemics but doesn’t shy away from present circumstances either. “I write from a personal place that’s definitely in the moment. I don’t go out of my way to use archaic language or anything,” says Prophet. “If you listen to my records, aside from the sort of vintage music going on, you’d think, ‘This guy knows what time it is [laughs].’ That’s my fantasy of myself! Like when Prince went on the Super Bowl and whipped out a Foo Fighters song. I’m not a Foo Fighters fan but I thought that was so hip. It was a way of saying [Prophet’s voice rising slightly], ‘Prince knows what time it is!’”

Homemade Blood

While it’s often easy to pick out a musician’s influences, it’s hard to get a clear grip on where Chuck Prophet came from. The man himself responds enigmatically, “Well, they’re out there [laughs]. You have to have faith in yourself. If something sounds derivative at first, as you kick it around it’ll morph into something of your own. Good writers, painters and artists tend to be pretty big fans of other people’s work. There’s filmmakers like Jim Jarmusch who are also great music fans. And there are great guys in music that are great fans of film, and painters who can only paint when they listen to music. There’s inspiration outside of your chosen field.”

This spills into a discussion of Jerry Garcia’s love of painting, which he’d done all of his life but only shared publicly in his later years. “He was an incredibly creative guy, a complicated dude, actually, though not when he was selling ties at Bloomingdales,” cracks Prophet. “I’ve worked with some musicians who worked with Garcia and they all described him, out of everybody, as the guy who was out of the house ten minutes after the alarm went off. He loved the creative process.”

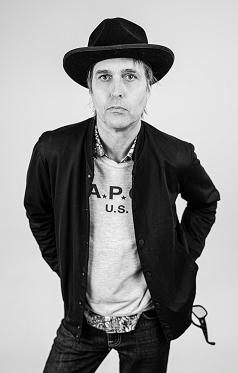

Prophet, a native Californian, was born and raised in Orange County until he was 16, then moved to San Francisco after college and currently resides in the Lower Haight area. Prophet’s live shows have a healthy pinch of the Garcia Band’s good time swing and instant bonhomie, where the playing is superb but they never forget they need to engage your feet, too. A couple years back at High Sierra, Prophet played twice in the same day, offering totally different moods that fit the Vaudeville Tent and Big Meadow, respectively, to a tee. Like Garcia, he knows how to read a room and give it just what it craves, even if they didn’t know what that was going in.

It doesn’t hurt that Prophet is a bonafide guitar shredder capable of Beatles-like eloquence and brevity as well as the bold expression and playful pyrotechnics of Tom Verlaine (Television) and Richard Thompson.

“I definitely got my head fucked up when I first heard Richard Thompson. No doubt about it,” Prophet says. “It just all came together for me when I heard his records from the ‘70s especially. I like how he wrote from his own voice and could go from this weird bagpipe thing straight into a Chuck Berry lick. I would probably sit on the Chuck Berry lick and just hint at something else. I’m an inverted version of that [laughs]. If Richard hadn’t been such a great record maker, songwriter and singer then I don’t think I’d have been as drawn into his guitar playing. That other stuff came first. You wouldn’t hang around for the guitar if not for the other. The reason I heard Marc Ribot was because I listened to those Tom Waits records and hung around for the guitar breaks. I think most of the guitar players I like are singers like Jimi Hendrix and Tom Verlaine. That’s why I love Chuck Berry so much. Everything he does punctuates his songs, it’s all one thing.”

Men frequently struggle to articulate their feelings and thoughts about women. Even the best songwriters often unconsciously veer into misogyny or thickheaded simplicity (see Dylan’s oddly beloved and oft-covered “Just Like A Woman” for an examples of both). Prophet manages to spring over these pitfalls, writing woman odes that use the distaff among us as genuine muse for tunes of real depth.

“It’s a delicate thing,” cautions Prophet. “There’s a delicate thing to the blues where it can go either way, where you can go downwards or celebrate the glory of having the blues. It’s a glorious thing to have the blues because it starts with love. It’s better to have your heart broken than to never have loved at all. That’s the part you have to stay in touch with if you want to sing these songs over and over again.”

His songs openly acknowledge the sway women have over many of us boys in a very honest way. “Yeah, absolutely,” enthuses Prophet. “On ‘A Woman’s Voice (Will Haunt You)’ [from Soap and Water] I cut verses. I have an editor’s sense to take out the parts that I didn’t think were true, even though they sounded really good [laughs].”

While women remain central to Prophet’s creative process, he’s often pretty solitary when working up new material.

“I don’t really run it by people. I’m superstitious,” says Prophet. “When I’m in the process of writing a song I don’t go out of my way to solicit anything. I’m just happy when it’s fucking over. At a certain point that’s enough. They take up space in your psyche. Some songs can be really difficult. It’s almost like I don’t feel like starting them but it feels good when they’re finished.”

Taking his time means that what ultimately emerges has a craftsmanship and sturdy endurance that stays around for decades. It’s a trait missing from a lot of modern rock, which too often has the staying power of Pop Rocks. Shortsighted rockers could never come up with a chilling lyric like, “I always did the right thing, what did it get me?”

“[laughs] I love that line, too. I really do. That might be my favorite part of the record, that bridge [on ‘Let’s Do Something Wrong’],” says Prophet, who excels at lines you can’t walk away from once you’ve been exposed to them. “It’s a fun character study of someone who always played by the rules and never left his small town. I think what makes the song really come together is the children singing, ‘Let’s do something wrong, let’s do something stupid.’ They sing it in such an earnest way because they don’t understand the implied costs, the repercussions as an adult for all your actions. When they sing, ‘Let’s do something wrong, let’s do something stupid,’ they sing it with all their heart and soul, without any sense of regret.”

For many older fans, Prophet will always be associated with Green On Red more than any of his ten solo records. While the band does the occasional reunion gig it does seem fraught with the kinds of regrets Prophet was discussing. “It’s like spending a weekend with the kids from your first marriage [laughs]. It’s a mixed thing,” admits Prophet. “We did one show and we were all really surprised how fun it was. We’ll do it from time to time.”

For now, his focus is his own work, a quiet, ceaselessly excellent string of recordings and performances that speak for themselves. All the praise in the world can’t measure up to the intrinsic pleasures awaiting one, in both the long and short term, inside Prophet’s music.

“I feel like I’m just getting the hang of it, so I hope I’m getting better. It’s hard [to get records into people’s hands] but my biggest fear is that I would have to stop. Ultimately, that’s the thing any artist fears more than anything,” says Prophet. “Economically, none of this has ever made any sense for me but you just make the records and play the shows. That’s really all there is to do.”

3_238_159auto_s_c1.jpeg)