[The following interviews are transcribed from John Sekerka’s radio show, Tape Hiss, which runs on CHUO FM in Ottawa, Canada. Each month, Cosmik Debris will present a pair of Tape Hiss interviews. This month, we’re proud to present an interview with Chuck Prophet, formerly of Green On Red, and from the Tape Hiss vaults, a 1992 interview with the tragically under-heard instrumental band, Pell Mell.]

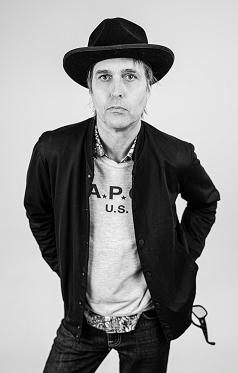

CHUCK PROPHET

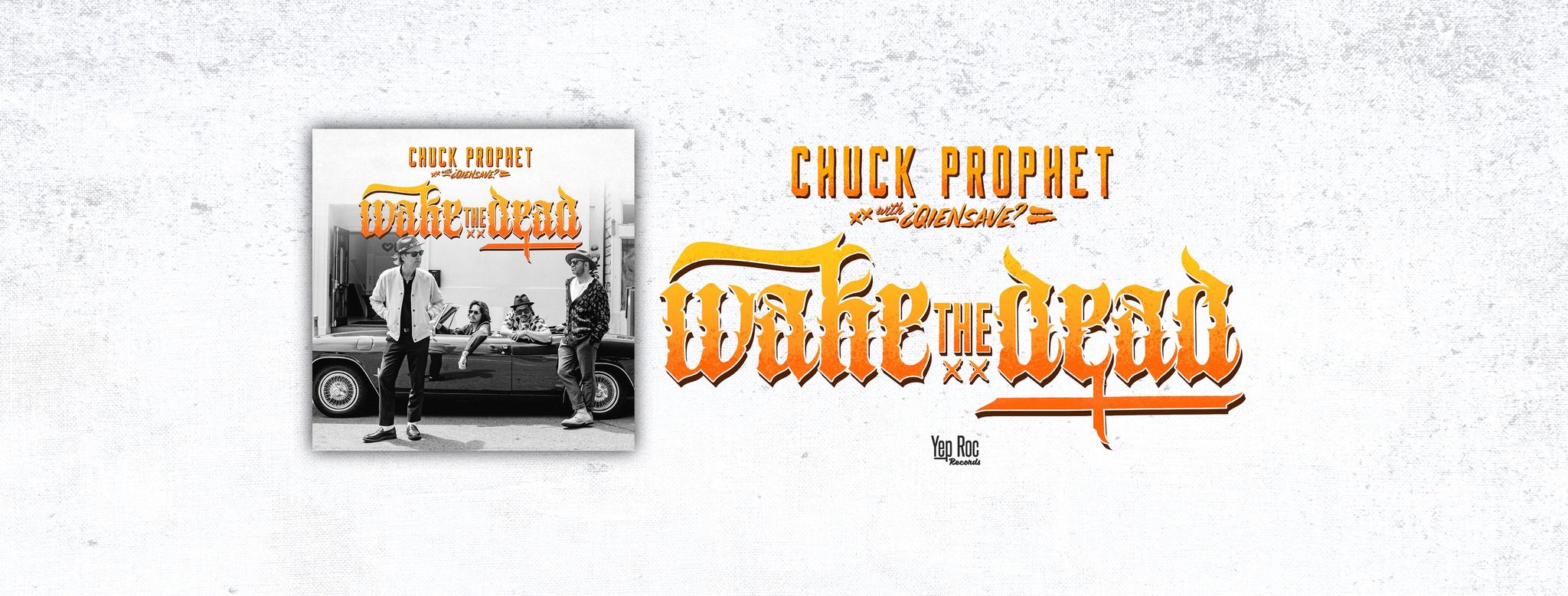

Green On Red were one of the ground breaking pioneers of cow punk, the thing that’s all the rage nowadays with bands like Sun Volt and Wilco. A band born a decade too early, they managed to lay down some criminally overlooked albums. Guitarist Chuck Prophet has emerged from the ashes with a nice collection of solo recordings, culminating in this year’s earthy “Homemade Blood”. From a San Francisco studio , Chuck talked about the old days, the new days, LSD trips, suburbia and dealing with the dictatorial producer, Steve Berlin. We also had an argument over a classic album.

JOHN: What’re you working on?

CHUCK: I’m just putzing around. I have to go to the studio and pay people to hang out with me. My lifestyle: friends and making records are all intertwined.

JOHN: Are you a musician seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day?

CHUCK: Yeah, but I don’t take it to bed. It could change any day. I could be down on Montgomery Street at six in the morning trying to sell flowers. I’ve thought about it.

JOHN: Let’s get to it: I quite like your new record, Homemade Blood. Compared to Brother Aldo, which was a more gentle, countrified album, it sounds like you just wanted to rock out.

CHUCK: Oh sure, sure. I was less interested in the process of making a record. I just wanted to get five people together, keep it simple, kicking the songs around, and trying to stick ‘em to tape with as little fuss as possible. You can hear people talking to each other on the record. The last record I made was with Steve Berlin [Los Lobos], and it was a bit involved. He couldn’t resist the temptation to put his fingerprints on anything and everything. He was running around with a flashlight, looking at what he could tweak. I just got a little tired of the process, you know? I like to ride. I like to get up and do something creative every day, and I wanted this record to be more of a live situation. Not that there wasn’t a lot of blood on the floor after I beat up the songs.

JOHN: I hear ya. It sounds like you got a little dirty. The press likes to pigeonhole you with a Rolling Stones sound, but what I hear is a bit of Tom Petty and The Replacements. Do labels offend you?

CHUCK: Naw, I also bear a resemblance to Tom Petty. I blame my parents. I don’t mind. The Stones, The Replacements - they’re just taking traditional stuff that’s laying around and turning it sideways. And that’s pretty much what I’ve always done.

JOHN: Do you know when you’ve nicked a riff, or does it sometimes come to you later?

CHUCK: Ah, I just ignore it and hope it goes away. I heard Keith Richards once held up an album for two months cuz he thought it [the nick] was gonna come to him. I used to pole vault over those mouse turds, but now I just walk through ‘em. I don’t care. By the time you beat up a song, take it through changes, if it’s still living and breathing by the time you stick it to tape, usually it’ll just go away. The initial riff or whatever it was that sparked the place in the back of your mind that made you think of sitting in the car with your Mom listening to Glenn Campell. They just go. It’s something in the subconscious editing process.

JOHN: How often do you write songs? Do they come to you, or do you tinker in the studio until something evolves?

CHUCK: I collect stuff, and every once in a while I’m lucky enough to get up in the morning and pull one out from the roots. Sometimes I gotta drag someone along. I do a lot of co-writing. Other times, I’ve written out of necessity, but those are never that good.

JOHN: Is there a difference making music in L.A. [Gun Club] and making music in San Francisco?

CHUCK: There’s music in the air in L.A., and I grew up in a time where music was coming from every car. It was everywhere. I took that for granted. I dunno if you get that everywhere. Living in San Francisco now - there’s an artistic thing in the air here that’s left over. It’s kinda cool. I don’t think they would have put up with The Grateful Dead in L.A. Some people say music’s all about geography - Jim Dickinson says the reason that the grooves are so sticky and greasy in Memphis is because the air just hangs heavier, all that humidity. There might be some truth to all that stuff.

JOHN: Dickinson produced Green On Red didn’t he?

CHUCK: Yeah, he’s the guru of voodoo. I’ve seen him do so many things that were invisible, just by being in the room. He’s a real presence. We did a live recording together in ‘94 which was bootlegged and is now on a French label.

JOHN: What label is that?

CHUCK: Last Call. It’s run by a fella who used to run New Rose, which was famous for putting out records by people who were dead, half dead, on the way up or on the way down.

JOHN: A great label. What is the official status of Green on Red anyway?

CHUCK: I dunno. We broke up every six months. We like to say that we went on strike. We’re still entertaining offers.

JOHN: So you keep in touch with Danny Stuart?

CHUCK: Yeah, I talk to him occasionally. He might leave a cryptic message on my machine recommending some conspiracy book or another.

JOHN: Can you reveal who wrote what in Green On Red?

CHUCK: Most of the time Danny carried away the writing. I might bring in something, a riff with words attached and we would run with it. Sometimes I’d bring in something that was completely finished.

JOHN: So this lyrical side of you is a new thing?

CHUCK: Naw, I’ve always written songs. You know writing with Danny was great. He’s fearless. He’d put a lot of things in songs that normally wouldn’t be in songs. He had a song about a guy with an enormous foot who made his living traveling in a minstrel show.

JOHN: I’m a big fan of Green On Red, especially “The Killer Inside Me” record.

CHUCK: Well you’re the only person who liked that record. We thought that it was just miserable.

JOHN: I’ve read that. Why do you think it miserable?

CHUCK: Well it was miserable making it. We thought that we were so bad-ass, so reactionary, and Danny had so much anti-establishment rhetoric. When we tried to make a record that actually rocked, we couldn’t rock to save our lives. I don’t know what it was. We were trying to make a ZZ Top record or something. It was like the Kingston Trio trying to jam with Robert Palmer. It just didn’t work. It was really bombastic, cold and overblown, and underneath it all were these tired, lackluster performances.

JOHN: But I love that record!

CHUCK: Maybe that’s what makes it exciting, but I don’t wanna listen to it.

JOHN: Really? The lead off track, “Clarksville,” is a total killer.

CHUCK: Yeah? Maybe we should stop apologizing and start a rumour that it’s a masterpiece… [pause] ...That record is a MASTERPIECE!

JOHN: Now you’ve got it. Were you guys fighting in the studio at the time?

CHUCK: Nobody cared enough to get that upset. We cut way too much stuff. Half of it had a sense of humour, it was kinda playful, and the other half was pretty bombastic. There were two records in there, and they were fighting each other.

JOHN: You know the CD version also has the No Free Lunch EP on it, so there are THREE records fighting it out!

CHUCK: There’s also an Australian bootleg which we authorized, that has all the outtakes. So if you’re such a sucker for punishment…

JOHN: Why go from Green On Red to solo work?

CHUCK: Well, I kept writing and playing outta necessity, outta habit. Luckily there was this bar called The Albion at the end of my street, and we could take it over on Friday and Saturday nights. These songs just appeared, and I thought I should get ‘em outta my head and on tape. I thought I was outta the music business. I was twenty-four years old, and I figured I got my shot. I was naive, thinking that cassette would be publishing demos. The tape got into the hands of some dude in England who decided it would make a record, and that’s what Brother Aldo was.

JOHN: Green On Red was always more popular with the British press. Is that still the case?

CHUCK: I suppose. We just spent more time over there cuz we got signed to a British label in ‘86 or something. They only see so far in front of their faces, so we ended up on the cover of Melody Maker and Sounds. By the time we were done over there, we were too tired to work back here.

JOHN: That was a great time for cow punk, back in L.A. with you, The Gun Club, The Dream Syndicate, X ... Was that a close knit community?

CHUCK: We crossed paths, though we never shared a house or anything.

JOHN: Do you carry a guitar with you at all times?

CHUCK: Naw, not really. A friend of mine is like that though. He was doing sixty days in county jail, so he made a guitar outta cardboard to keep him company.

JOHN: How would he play it?

CHUCK: He just moved his hands, knowing how it would sound. I’m thinking of making one - my neighbours would love it.

JOHN: Do you get written up and fawned over by guitar magazines?

CHUCK: Yeah, I get the obligatory piece with every record.

JOHN: How do you find that almost geeky worship? Is that a bit embarrassing?

CHUCK: It’s kinda fun, cuz the rest of pop culture has become too intellectual. It’s great to talk about Russian guitar pedals for a change.

JOHN: For all the guitar geeks out there, could you outline your latest gizmo?

CHUCK: Well, I’m really into this thing called an envelope follower. It plays whatever you’re playing an octave lower, and if you hit it harder - it’s touch sensitive - it bubbles like lava up an octave. It’s really painful.

JOHN: Painful to hear or to play?

CHUCK: Painful for everybody in the room - when it explodes. It’s really cool.

JOHN: Let’s get back to the new record. On the very catchy “Ooh Wee,” you mention being strung out on ritalin and colour TV at nine years old.

CHUCK: Wasn’t everybody?

JOHN: Damn right. Growing up in L.A. in the early seventies must have been pretty wild.

CHUCK: I was lucky enough to have an older sister who got into a lot of trouble.

JOHN: Were all your experiences second hand then, or did you find trouble yourself?

CHUCK: We don’t have that kinda time.

JOHN: We don’t? You must have one story you can sneak in here.

CHUCK: I was arrested and thrown in jail, peaking on two hits of LSD. But the story itself is kinda boring unless you were there. There is a moral, though: you gotta fix those parking brakes and things, else you get pulled over.

JOHN: Listening to “Homemade Blood” I get a feeling that you write about mid-America - some might call it suburban white trash - not condescendingly, more as an observation of the lifestyle.

CHUCK: The last couple of records were influenced by my immediate surroundings. Certain events led me back to living with my folks in the suburbs. There’s a photographer, Bill Owens, who took pictures of suburbia developments in the seventies. I saw his pictures in a museum and I got into that. And when I got back home everything had changed. The Dairy Queen was gone. I found myself bumping into ghosts, and some ended up in my songs.

3_238_159auto_s_c1.jpeg)